John Paton Davies’s China Hand: An Autobiography, the posthumously-published 2012 winner of the American Academy of Diplomacy’s annual Douglas Dillon Award for distinguished writing on the conduct of U.S. diplomacy, is one of the best diplomatic memoirs we’ve read in years.

Davies, who died in 1999 at the age of ninety-one, is best known as one of the most prominent of the State Department China-specialists who were hounded out of the Foreign Service during the McCarthy era because of their alleged sympathy for the Communists in the Chinese civil war. But his memoir includes more than recollections of his experiences in China. A fascinating surprise, for readers interested in South Asia, lay in its accounts of his meetings in India in 1942-43 with top leaders of the independence movement at a crucial period in their struggle against the British Raj. His spirited, well-written reports of his talks with these prominent figures, his incisive observations of their personalities, and his analyses of other salient features of the contemporary Indian political scene add an important dimension to his book. They provide fresh insights into the way Indian leaders viewed their struggle as well as their – and Davies’s – assessments of what the United States was doing and should do in the Indian subcontinent in those years.

Davies was born into a missionary family in China and had served at several U.S. diplomatic posts there before returning to the country only weeks after Pearl Harbor as a middle-grade Foreign Service officer on the staff of General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, the commander of U.S. forces in the China-Burma-India Theater headquartered in Chungking, China’s wartime capital. There he shrewdly concluded that he could be most useful to the general, surrounded as Stilwell was by China experts, if he made India his specialty. He confesses that at the time he knew virtually nothing about the country aside from the little he had picked up from the writings of Kipling and E.M. Forster. That handicap did not deter him. With Stilwell’s approval he headed over the hump for India in May 1942.

Once there, Davies soon went well beyond the Indian contacts American officials in New Delhi and Calcutta arranged for him. He writes that he wanted “to go further afield, to other parts of India, and to meet influential Indians outside the diplomatic circuit, especially the troublemakers.” He was convinced that his unusual posting to General Stilwell’s staff gave him an accepted standing in the country that would allow him to seek out Indians with whom his Foreign Service colleagues posted there on regular assignment could have little or no contact.

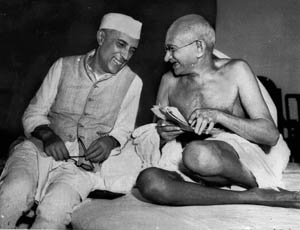

As a diplomatic second secretary Davies, then thirty-four, was only a mid-level officer. But he was never shy in reaching out to the top leaders of the independence movement. The Indians, for their part, seemed to welcome his overtures and readily met with him, many of them in repeated sessions. His list of contacts is stunning for someone of his rank. Headed by Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Mohammed Ali Jinnah, it included a wide variety of other leaders who like them would become prominent figures in independent India and Pakistan. None of them seemed to stand on ceremony; they dealt with Davies’s searching questions willingly and with considerable if not total candor despite his modest official diplomatic standing.

Davies usefully quotes letters, reports and diary entries he wrote at the time. These make for compelling and often entertaining reading. Filled with insightful analyses of political events and shrewd descriptions and character sketches of the people involved, they are diplomatic reporting and analysis of a very superior quality.

Davies’s first major contact with political India came when he barged uninvited into a crucial session of the Indian National Congress Working Committee in Allahabad in May 1942. He listened as the members – “who only five years later would govern India” – argued over the strategy the party should follow in its dealings with the British raj, the Muslim League, and a prospective invasion by the Japanese Army. No one seemed to object to his presence. He was later able to set up private meetings with some of the main players in the session, who elaborated on their working committee speeches for his benefit.

Davies seems to have been particularly taken by C. Rajagopalachari, a future governor general of India whom he found clever and pragmatic. Displaying his knack for vivid description that is a delightful feature of the book, Davies calls Rajaji “a frail little man with slender hands, the palms of which were dyed lavender.” He was less impressed by future prime minister Nehru, in his words “a glamorous super-Brahmin,” a “bicultural…elegant, intellectual, ornamental aristocrat” with a contradictory, indecisive personality. These and other major leaders conversed with Davies in excellent English. But in the Working Committee session itself he was amused that those who spoke in their own regional languages often sprinkled them with English phrases. These, he recalled, included “popular mandate, wishful thinking, and child psychology.” Some aspects of Indian political meetings never change!

Gandhi himself was not at the Allahabad session, so Davies sought him out first at his ashram in Central India and then in Bombay, where he held a long conversation with the Mahatma. He reported to General Stilwell that he had begun the discussion by asking Gandhi what he thought the United States could do to be helpful to India. “Persuade the British to withdraw immediately and completely,” Gandhi replied. The Mahatma then explained that once the British had left there would be no incentive for the Japanese to attack since their primary objective in that part of the world was the destruction of British power. A long, fascinating argument followed. Davies had no qualms about taking on the venerable leader and sharply questioning his assumptions. Gandhi, for his part, told Davies that he did not believe the United States might exert its good offices on behalf of India because “American diplomacy was under the control of the British and…the voice of Americans in the United States friendly to India was being stifled by the British.”

Davies went well beyond the Congress party leadership in his search for understanding of the contemporary Indian scene and sought out senior figures across the political spectrum. Mohammed Ali Jinnah figured prominently among them. After several conversations with the future founder of Pakistan, Davies commented in a January 1943 message that he was “as astute and opportunistic a politician as there is today in India. [He] fulfills the role of fuehrer called for by the circumstances the Muslims found themselves in. He has skillfully exploited the apprehensions of his community and has built up the Muslim League as a disciplined organization obedient to his will.” Davies accurately called Pakistan, Jinnah’s battle cry, a “vaguely defined program.”

Another future leader of Pakistan whom Davies came to know well was Ghulam Mohammed, a top official in the British Indian government who in the 1950s became the powerful governor general of the Muslim state. Like Rajaji and some other Indians whom Davies drew out on the subject, Ghulam Mohammed asserted that American solidarity with Britain at the expense of the independence of India and other colonies would eventually lead to international conflict on the basis of color.

Comments like this heightened Davies’s strong concern that Washington’s continued backing for Britain’s efforts to hold on to India following the end of the war and American support for the British, Dutch, and French as they sought to return to their colonies in Southeast Asia at that time could pose a major problem for the United States. He told Stilwell in January 1943 that “we [Americans] have come to be associated with the British. That was in part because of American silence and inaction about British imperialism in India, giving the impression that the United States at least tacitly supports it.” Davies warned that “India in [postwar] revolt against persisting white imperialism might well attract the practical interest if not sympathy of the Soviet Union, or China, or both.”

Davies argued that Washington must dissociate itself from British imperial policy. He wanted it to stop supporting Britain’s control over India and its efforts to regain its lost colonies in Southeast Asia. He recognized that going further than this—seeking to induce London to set in train an orderly relinquishing of sovereignty over India in favor of an eventual independent Indian government — would be offensive to the Churchill government then in power. But he concluded that such American intervention was justified because of the heavy postwar risks arising out of a British attempt to hold India. In his view, these risks would strongly affect the United States. He asked rhetorically – and dramatically– “can we afford …to let the British run the risk of losing us the peace?”

As he recognizes in his memoir, these fears of postwar imperialist struggles in Asia did not materialize, at least not in the Indian subcontinent. (They did of course in Vietnam and Indonesia.) Instead, the British quit India in 1947, in Davies’s words “with consummate skill and statesmanship.”

Doing so, they left India (and Pakistan) in the hands of those very leaders Davies had so zealously cultivated and evaluated as a young, energetic, and enterprising American Foreign Service officer during the unusual assignment there he recorded so well in China Hand: An Autobiography.